Thanks to the local Historical Society, Clear Lake finally has its own history museum backed up by a history archives room at the public library (developed by H. Milton Duesenberg). These two resources are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to telling the full story. After reading just a sampling of their many history accounts, one can better see how this North Iowa tourist town is so uniquely connected to Iowa’s development story.

The route of U.S. Highway 18 (the first paved inter-city highway in Iowa, Mason City to Clear Lake) has since ancient times been a thoroughfare for Native Americans, traveling back and forth between the Omaha villages on the Missouri River and the Wisconsin Region tribes. It ran near Clear Lake’s elevated and abundant body of water. As far back as 1688, the French king sent a young military officer by the name of Lahontan to chart the course of this Chemin de Voyageurs (path of the voyagers). He was actually here to document and legalize, by name, the hundreds of French fur trappers who worked west from the Mississippi River. His survey notes were later officially documented in a 1718 map, designed by the royal cartographers — the De L’Isles of Paris.

The next person to take interest in this region was General William Clark (of the Lewis & Clark Expedition), who in 1832 needed a government survey completed of the Neutral Grounds. That was the unique swath of land across North Iowa which was ostensibly set aside to keep at bay the Sioux to the north and the Sauk & Fox tribes to the south, so that the Winnebago would have a safe refuge for hunting. The ideal man for the job was the surveyor son of Daniel Boone, Nathan. He took the commission and set out from Missouri with his own son, James, along with a small surveying crew plus Indian agents. He was required to blaze every tree near the boundary line and set a stake or build a mound at every half-mile. The first documented use of the name ‘Clear Lake’ appeared on Boone’s signed survey map. After having spent three days along the lake’s shores and trekking across a great part of Iowa, he was recalled by Gen. Clark because of the threat of violence in the impending Black Hawk war.

Some 18 years later, two itinerant buffalo hunters who had recently spent a season around the lake found themselves back in a Dubuque tavern boasting up the natural resources they had found, there. The pioneering entrepreneurs who took active interest in these accounts were a young farmer, James Dickirson, and experienced trail-blazer Captain Joseph Hewitt.

Hewitt was a bonafide Indian trader and friend to the Winnebago. He had run a trading post near Strawberry Point and learned the native language. He had been a commissioner on the official layout of the Old Mission Road from Dubuque to Fort Atkinson. He and Dickirson along with their wives, children and two hired hands started out for the mystical lake on May 20th of 1851. Haltered by two family wagons, a supply wagon and a flatboat skiff, they endured one of the rainiest spring seasons in Iowa history. Through muddy fields and swampy stream beds they had to utilize the skiff to make the crossing at numerous spots. It wasn’t until July 14th that they finally found their way, via the route of its drainage outlet, to the glistening shores of Clear Lake.

After a year of attempting to corral buffalo calves and start corn crops, they were eventually joined by two other families – the Sirrines. Hewitt and Dickirson came to realize that their true ambition wasn’t livestock and farming, but land development. Dickirson claimed property on the lake’s northeast corner, while Hewitt made plans for the settlement of Clear Lake City — south of the outlet.

Their community plans would be interrupted when several friendly Winnebago families moved in to be near Hewitt’s settlement. That act brought on a hostile contingent of 500 Sioux from Minnesota, who set up camp only eight miles away. Several months later, Patchoka, the 15-year old English speaking son of the Winnebago leader, was attacked while working with Hewitt’s horses. Two vicious Sioux warriors killed and beheaded him. The Winnebago families had to be hurried off for safety to Wisconsin via an “underground railroad” connection of wagon rides. While Hewitt bravely confronted the Sioux war party by himself, Governor Grimes sent a mounted rescue from Iowa City. The combined militia of soldiers and armed farmers pulled all of Clear Lake’s settlers back to Marble Rock, only to have their lakeside households get ransacked by roaming hunters and soldiers.

The town founders returned several months later to re-establish Hewitt’s Clear Lake City. Dickinson plotted out the neighboring town of Clear Lake Village and started work on the first general store, tavern and rooming house. He too had to fight off a band of belligerent Sioux who came in 1856 to harass his family. Then again a year later, 50 angry braves encamped with war dances in the town park that he had just donated to the community. A young James Dickirson brazenly confronted the Sioux enclave by himself, and sternly convinced them to leave the area for good.

In 1857, the Tuttle families platted a ‘town’ named Livonia on the (now cemetery hill) just northeast of Clear Lake Village. They were part of the leadership movement to get the Cerro Gordo County courthouse built there. This movement succeeded with a new court building and the transferral of court records. Yet, a year later the county court was petitioned to vote for potential relocation back to Mason City. The few Winnebago citizens were not allowed to vote, and Mason City held the count. Livonia would lose its identity. *Oral history tales note that the Livonia court house was soon burned down in the dark of night.

The Civil War decade saw slow growth around the lake, except for a few noteworthy advances. The first newspaper, The Independent, went to press (but only ran for about a year). Also, the island — the lake’s most unique feature — was signed over to private ownership by the U.S. government. This was verified by a document signed by President Lincoln in 1861.

With Joseph Hewitt losing his son in the Civil War, he too soon died after serving the area as the first mail carrier (covering an arduous route to Algona). The Sirrine families also lost two of their sons in the great conflict.

Yet, the decade ended on an up-beat note for the lake’s slowly increasing resident population. The first successful newspaper, The Observor, was started up. The railroad tracks and accompanying telegraph line finally arrived. Effective community leaders, such as mover & shaker George Frost, arrived at the lake. Even the first hints of serious tourism could be seen, along with the growing popularity of sailing on the lake.

In 1871 with the resident population at 800, the two villages were formally combined into the city of Clear Lake and was promoted as ‘having the best sidewalks in Iowa’.

By the next year, the island featured the first resort dwelling for the new guests. Named the ‘Island Home Hotel’ it bragged a bowling alley, a billiard room, lawn games and offered horse racing around its rocky shoreline.

The “foot of main” was the expression used to direct visitors to the boating liveries by the city beach. A rustic steamer ‘Lady of the Isle’ was the first excursion boat built by the island hotel proprietors to transport guests from the town dock. It was soon replaced by the more soundly built ‘Island Queen’ that was relied upon to move ever growing numbers of tourists to and from the hotel.

Clear Lake’s burgeoning sailing scene got its big boost in 1874 when the Green brothers set-up their sailing livery by the foot of Main Avenue. Alonzo and Delos were genuine Great Lakes sailing captains, who brought the large sailboat ‘Challenge’ from Chicago.

Tourism was becoming such a boom industry that professional photographers were brought in, initially by the Island Home Hotel, to shoot a variety of pictures for the newly popular stereograph viewers.

In 1875, after years of searching for the ideal location for a Midwest regional church camp, the Rev. John H. Lozier purchased 36 acres and a half-mile of north shoreline as the original Clear Lake Park. What was to follow through the subsequent summers was a religious and cultural camp experience of national note. A variety of hotels, tent camps, cabins and vendors were needed to accommodate the tens of thousands of pilgrims and summer vacationers who came to see and hear some of the most famous preachers, international performers and national civic leaders appearing in these “Chautauquas”.

The route of U.S. Highway 18 (the first paved inter-city highway in Iowa, Mason City to Clear Lake) has since ancient times been a thoroughfare for Native Americans, traveling back and forth between the Omaha villages on the Missouri River and the Wisconsin Region tribes. It ran near Clear Lake’s elevated and abundant body of water. As far back as 1688, the French king sent a young military officer by the name of Lahontan to chart the course of this Chemin de Voyageurs (path of the voyagers). He was actually here to document and legalize, by name, the hundreds of French fur trappers who worked west from the Mississippi River. His survey notes were later officially documented in a 1718 map, designed by the royal cartographers — the De L’Isles of Paris.

The next person to take interest in this region was General William Clark (of the Lewis & Clark Expedition), who in 1832 needed a government survey completed of the Neutral Grounds. That was the unique swath of land across North Iowa which was ostensibly set aside to keep at bay the Sioux to the north and the Sauk & Fox tribes to the south, so that the Winnebago would have a safe refuge for hunting. The ideal man for the job was the surveyor son of Daniel Boone, Nathan. He took the commission and set out from Missouri with his own son, James, along with a small surveying crew plus Indian agents. He was required to blaze every tree near the boundary line and set a stake or build a mound at every half-mile. The first documented use of the name ‘Clear Lake’ appeared on Boone’s signed survey map. After having spent three days along the lake’s shores and trekking across a great part of Iowa, he was recalled by Gen. Clark because of the threat of violence in the impending Black Hawk war.

Some 18 years later, two itinerant buffalo hunters who had recently spent a season around the lake found themselves back in a Dubuque tavern boasting up the natural resources they had found, there. The pioneering entrepreneurs who took active interest in these accounts were a young farmer, James Dickirson, and experienced trail-blazer Captain Joseph Hewitt.

Hewitt was a bonafide Indian trader and friend to the Winnebago. He had run a trading post near Strawberry Point and learned the native language. He had been a commissioner on the official layout of the Old Mission Road from Dubuque to Fort Atkinson. He and Dickirson along with their wives, children and two hired hands started out for the mystical lake on May 20th of 1851. Haltered by two family wagons, a supply wagon and a flatboat skiff, they endured one of the rainiest spring seasons in Iowa history. Through muddy fields and swampy stream beds they had to utilize the skiff to make the crossing at numerous spots. It wasn’t until July 14th that they finally found their way, via the route of its drainage outlet, to the glistening shores of Clear Lake.

After a year of attempting to corral buffalo calves and start corn crops, they were eventually joined by two other families – the Sirrines. Hewitt and Dickirson came to realize that their true ambition wasn’t livestock and farming, but land development. Dickirson claimed property on the lake’s northeast corner, while Hewitt made plans for the settlement of Clear Lake City — south of the outlet.

Their community plans would be interrupted when several friendly Winnebago families moved in to be near Hewitt’s settlement. That act brought on a hostile contingent of 500 Sioux from Minnesota, who set up camp only eight miles away. Several months later, Patchoka, the 15-year old English speaking son of the Winnebago leader, was attacked while working with Hewitt’s horses. Two vicious Sioux warriors killed and beheaded him. The Winnebago families had to be hurried off for safety to Wisconsin via an “underground railroad” connection of wagon rides. While Hewitt bravely confronted the Sioux war party by himself, Governor Grimes sent a mounted rescue from Iowa City. The combined militia of soldiers and armed farmers pulled all of Clear Lake’s settlers back to Marble Rock, only to have their lakeside households get ransacked by roaming hunters and soldiers.

The town founders returned several months later to re-establish Hewitt’s Clear Lake City. Dickinson plotted out the neighboring town of Clear Lake Village and started work on the first general store, tavern and rooming house. He too had to fight off a band of belligerent Sioux who came in 1856 to harass his family. Then again a year later, 50 angry braves encamped with war dances in the town park that he had just donated to the community. A young James Dickirson brazenly confronted the Sioux enclave by himself, and sternly convinced them to leave the area for good.

In 1857, the Tuttle families platted a ‘town’ named Livonia on the (now cemetery hill) just northeast of Clear Lake Village. They were part of the leadership movement to get the Cerro Gordo County courthouse built there. This movement succeeded with a new court building and the transferral of court records. Yet, a year later the county court was petitioned to vote for potential relocation back to Mason City. The few Winnebago citizens were not allowed to vote, and Mason City held the count. Livonia would lose its identity. *Oral history tales note that the Livonia court house was soon burned down in the dark of night.

The Civil War decade saw slow growth around the lake, except for a few noteworthy advances. The first newspaper, The Independent, went to press (but only ran for about a year). Also, the island — the lake’s most unique feature — was signed over to private ownership by the U.S. government. This was verified by a document signed by President Lincoln in 1861.

With Joseph Hewitt losing his son in the Civil War, he too soon died after serving the area as the first mail carrier (covering an arduous route to Algona). The Sirrine families also lost two of their sons in the great conflict.

Yet, the decade ended on an up-beat note for the lake’s slowly increasing resident population. The first successful newspaper, The Observor, was started up. The railroad tracks and accompanying telegraph line finally arrived. Effective community leaders, such as mover & shaker George Frost, arrived at the lake. Even the first hints of serious tourism could be seen, along with the growing popularity of sailing on the lake.

In 1871 with the resident population at 800, the two villages were formally combined into the city of Clear Lake and was promoted as ‘having the best sidewalks in Iowa’.

By the next year, the island featured the first resort dwelling for the new guests. Named the ‘Island Home Hotel’ it bragged a bowling alley, a billiard room, lawn games and offered horse racing around its rocky shoreline.

The “foot of main” was the expression used to direct visitors to the boating liveries by the city beach. A rustic steamer ‘Lady of the Isle’ was the first excursion boat built by the island hotel proprietors to transport guests from the town dock. It was soon replaced by the more soundly built ‘Island Queen’ that was relied upon to move ever growing numbers of tourists to and from the hotel.

Clear Lake’s burgeoning sailing scene got its big boost in 1874 when the Green brothers set-up their sailing livery by the foot of Main Avenue. Alonzo and Delos were genuine Great Lakes sailing captains, who brought the large sailboat ‘Challenge’ from Chicago.

Tourism was becoming such a boom industry that professional photographers were brought in, initially by the Island Home Hotel, to shoot a variety of pictures for the newly popular stereograph viewers.

In 1875, after years of searching for the ideal location for a Midwest regional church camp, the Rev. John H. Lozier purchased 36 acres and a half-mile of north shoreline as the original Clear Lake Park. What was to follow through the subsequent summers was a religious and cultural camp experience of national note. A variety of hotels, tent camps, cabins and vendors were needed to accommodate the tens of thousands of pilgrims and summer vacationers who came to see and hear some of the most famous preachers, international performers and national civic leaders appearing in these “Chautauquas”.

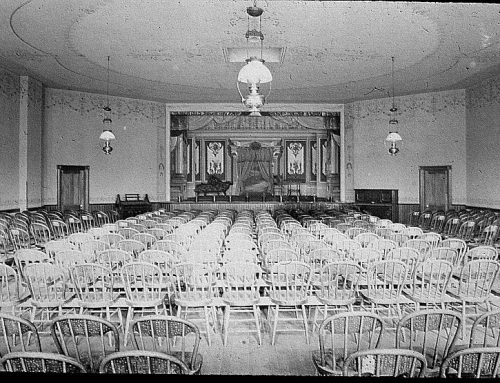

The two structural gems of this long-running experience were the campground’s auditorium pavilion, which could hold hundreds of people. (It sat across from the original railroad depot on high ground that is now D.A.R. Park.) Also, the regal Oaks Hotel that could be reached by trolley cars from Mason City, drew people from every New England city. (Having burned down in 1922, it is now – 2025/2026 – being rebuilt to much of its original status as part of the new Surf District complex.)

Indeed, Clear Lake would be marketed, very successfully, to Easterners as ‘the Saratoga of West’. Yet, from the direction of Council Bluffs came Nathan P. Dodge and eventually his brother General Granville Dodge who were drawn by the competitive sailing opportunities. Their summer home acreage was eventually developed into exclusive lots on the south shore that is still named after them – Dodge’s Point.

Even the winter freeze brought opportunity to the lake. Once a railroad sidetrack was put in place in 1878 to handle the harvesting of lake ice, a new industry was born. Warehouses and rail cars were loaded with giant sheets of block ice that would stay frozen through the summer months. It allowed for “refrigerated” train cars to haul meat and produce to markets as far away as St. Louis and Kansas City.

The next boom for the little city included grain elevators, fine dining restaurants, Turkish spas, large cattle ranches that sent trainloads of beef to Chicago, lakeside bathhouses with water slides, and even a classy opera house.

The state’s first condominium complex, the Outing Club, was built as a massive common cottages unit to house the association of families who came for the annual summer “Chautauqua” programs. Their private dining hall even featured live bands during evening meals.

By 1897 nothing had enhanced the summer excursion traffic as did that year’s arrival of the interurban railroad and downtown trolley line. It would endure to become the longest operating electric interurban rail system to haul freight in the U.S. *(Photo: caption identifying it as the “Mason City & Clear Lake Traction Company”)

By the turn-of-the-Century the foot of Main was bustling with competing boat liveries, celebrity guests on the Chautauqua circuit, a new sawmill, and the first of an annual 4th of July parade with carnival.

In 1903 Whitaker’s Covered Dock became the talk of the regional tourism industry. This impressive pier arcade and dancehall sat majestically out over the cooling waters of the lake. It even had a bowling alley on its lower level. Bands from all over the Midwest made stops, there. *(Photo: caption stating how the lake waves had soon damaged the building)

Vacation stays at the Grandview Hotel on the south shore palisades had become such a popular tradition that the newly formed Oakwood Park Company purchased the hotel and its 220 woodland acres in 1906. [Its centerpiece hotel would change its name to Oakwood Park Hotel in 1907.] Attractions on the south side of the lake were then beginning to compete with the downtown facilities on the north shore.

Most of that attention was centered around the Bayside Amusement Park that was built, facing the island. This created a profound increase in tourist boating excursions across the lake. This family fun park, the first of its kind for hundreds of miles, had a wide variety of novel attractions and activities that would rival a small theme park of today. It eventually hosted the baseball stadium for the semi-pro Bayside Cubs. This thriving entertainment venue held its own as far as quality attraction, during the Roaring Twenties. *(Photo of roller coaster: with caption listing many of the attractions)

Then, after Whitaker’s Pier had to be torn down due to so much water damage, the north shoreline saw a succession of famous and infamous nightclubs and ballrooms that would draw patrons and performers from all over the country. Many a tourist valued an entertaining night at Young’s Idleo, the White Pier, the Electric Theater, the Tom-Tom, and the Surf Ballroom & Roof Gardens.

No other town in the Upper Midwest has had so many entertainment venues come and go through the years. So many other accomplishments and unique happenings took place during these times, that one needs to view the Clear Lake history documentary “Stories from the History Room” in order get the full story. It is available through the Clear Lake Historical Society at CLIowahistory@gmail.com.

Even the winter freeze brought opportunity to the lake. Once a railroad sidetrack was put in place in 1878 to handle the harvesting of lake ice, a new industry was born. Warehouses and rail cars were loaded with giant sheets of block ice that would stay frozen through the summer months. It allowed for “refrigerated” train cars to haul meat and produce to markets as far away as St. Louis and Kansas City.

The next boom for the little city included grain elevators, fine dining restaurants, Turkish spas, large cattle ranches that sent trainloads of beef to Chicago, lakeside bathhouses with water slides, and even a classy opera house.

The state’s first condominium complex, the Outing Club, was built as a massive common cottages unit to house the association of families who came for the annual summer “Chautauqua” programs. Their private dining hall even featured live bands during evening meals.

By 1897 nothing had enhanced the summer excursion traffic as did that year’s arrival of the interurban railroad and downtown trolley line. It would endure to become the longest operating electric interurban rail system to haul freight in the U.S. *(Photo: caption identifying it as the “Mason City & Clear Lake Traction Company”)

By the turn-of-the-Century the foot of Main was bustling with competing boat liveries, celebrity guests on the Chautauqua circuit, a new sawmill, and the first of an annual 4th of July parade with carnival.

In 1903 Whitaker’s Covered Dock became the talk of the regional tourism industry. This impressive pier arcade and dancehall sat majestically out over the cooling waters of the lake. It even had a bowling alley on its lower level. Bands from all over the Midwest made stops, there. *(Photo: caption stating how the lake waves had soon damaged the building)

Vacation stays at the Grandview Hotel on the south shore palisades had become such a popular tradition that the newly formed Oakwood Park Company purchased the hotel and its 220 woodland acres in 1906. [Its centerpiece hotel would change its name to Oakwood Park Hotel in 1907.] Attractions on the south side of the lake were then beginning to compete with the downtown facilities on the north shore.

Most of that attention was centered around the Bayside Amusement Park that was built, facing the island. This created a profound increase in tourist boating excursions across the lake. This family fun park, the first of its kind for hundreds of miles, had a wide variety of novel attractions and activities that would rival a small theme park of today. It eventually hosted the baseball stadium for the semi-pro Bayside Cubs. This thriving entertainment venue held its own as far as quality attraction, during the Roaring Twenties. *(Photo of roller coaster: with caption listing many of the attractions)

Then, after Whitaker’s Pier had to be torn down due to so much water damage, the north shoreline saw a succession of famous and infamous nightclubs and ballrooms that would draw patrons and performers from all over the country. Many a tourist valued an entertaining night at Young’s Idleo, the White Pier, the Electric Theater, the Tom-Tom, and the Surf Ballroom & Roof Gardens.

No other town in the Upper Midwest has had so many entertainment venues come and go through the years. So many other accomplishments and unique happenings took place during these times, that one needs to view the Clear Lake history documentary “Stories from the History Room” in order get the full story. It is available through the Clear Lake Historical Society at CLIowahistory@gmail.com.

The History Room at the Clear Lake Public Library is the open-to-the-public depository that has documentation on hundreds of accounts that are worthy of national interest.

Written by Greg Wm. Schmidt